Internet Matters as an organisation

We are an independent not-for-profit organisation created and funded by industry to help children benefit from connected technology safely and securely. We invest heavily in understanding parents and carers views on a range of online safety issues. We do this through polling 2,000 parents of 4-16-year olds three times a year. In addition to that polling, we also ran a 5-day online community for teenagers and parents to understand their experience of gaming. All of these findings can be found in the Parenting Generation Game Report and the different methodologies explain why some comments have data points and some are conclusions from sentiments.

Children and young people experiencing vulnerabilities more likely to spend on loot boxes

Of course, not all parents are the same, and the primary driver for differences of opinion is the age of the child. However, interestingly for this research, there were statistically significant differences of opinions between mums and dads. Equally, it is important to note that vulnerable children will experience online spending and loot boxes differently. Due consideration should be given to young people facing offline vulnerabilities as they over-index as gamers who ‘often spend quite a bit of money in online games’. Data from the 2019 Cybersurvey indicates that whilst 15% of non-vulnerable children agree with this statement the figures increase to 29% of children with speech difficulties, 27% of care experienced children, and children with anger issues and 26% of children with eating disorders. These data points tell us that children with vulnerabilities are significantly more likely to be often spending what they regard as quite a bit of money.

In the consultation, you ask a number of questions about the harms linked to loot boxes and online spending. Please find our responses below:

Question a. What are the harms and how are they caused by loot boxes?

In the course of our online community parents told us they were concerned about the normalisation of gambling behaviour through loot boxes – see Parenting Generation Game Report, page 36. The nature of these purchases means children are being introduced to a form of gambling at a very young age. Parents worry about the implications of normalising these purchases and the kind of betting behaviours this could encourage for their child in the future.

“Again, loot boxes are very common in Fortnite and ‘packs’ in FIFA are a similar product. It’s down to chance how good the contents are which effectively is a form of gambling”. Dad, with son, aged 13

It’s worth noting that our research was completed before the Gaming Industry commitment to transparency of probability in loot boxes was published, and we expect parents would welcome this initial step.

Question b. Whether young people are impacted differently to adults, and if so, how?

The gambling element of loot boxes drives a number of related concerns for children. Parents tend to teach their children about fairness and transparency in social transactions – about keeping your word and doing what you say you will. That doesn’t happen in loot boxes; the transaction is lopsided, rather than equal, and precisely because of the unknown element, loot boxes train our children to invest for an intermittent reward. The risk here is that neuron connections are formed in developing brains, which becomes habit-forming. So, whilst the reward provides a momentary glut of ‘feel-good factor’, the flip side of dopamine is that it becomes habit-forming. Add to this that gaming often rewards competency and loot boxes can allow faster game progression, and children, like adults, have a tendency to remember the wins and forget the losses, we have a toxic cocktail of unequal engagement offering intermittent rewards, which becomes habit-forming in an environment of selective amnesia. That doesn’t describe a situation in which the interests of the child are given primacy and their rights to safe online spaces are well respected. We wouldn’t want to go as far as to say that all online spaces should be created for children as adults to have rights to find enjoyment and escapism online, but nonetheless, children enjoy a right to safe spaces.

The next area of concern is the value of intangible assets. Most in-game purchases are not physical items and therefore only exist within the game, for some parents spending on these games can be seen as a waste of money. Not having something tangible can be an unusual concept for parents to accept. One Mum told us she sees spending in games as ‘dead money because she (the daughter) has nothing to show for it’. If you consider an offline equivalent creating a theme park that children flock to alone and ask them to spend money to enjoy a more intense thrilling ride, perhaps without a seatbelt, would raise some concerns – so it’s good that we are questioning them online too.

Parents are also concerned that children are dealing with the pressure to purchase when they don’t understand the value of money, and so cannot be in a position to make informed decisions. These issues could be addressed if children were taught about value consumption perhaps through teachable moments around pocket money or gifts, but parents will want to do this in their own way, not because an online game has created a situation they need to address.

The persuasive design element of games and loot boxes must also be considered. Gamers are engaged in a tug-of-war between themselves and the arrayed ranks of psychologists that have developed the game, testing every colour, sound and reward mechanism to ensure it’s compelling. That’s a significant amount of expertise we are asking our children to resist, in real-time, with a world of social pressure. It’s simply not a fair fight. How much better could it be if all of those persuasive design elements were deployed for positive reasons. Not to rob the game of any joy, but simply to direct positive outcomes, like reminders to take a break every 30 minutes and perhaps time-outs after longer periods of gameplay.

Question c. Whether any harms identified also apply to offline equivalents of chance mechanisms, such as buying packs of trading cards.

Whilst there are undoubtedly parallels between trading cards and online chance mechanisms, in terms of the social status they confer, the key difference is the immediacy of the decision-making process required in an online game. There is no opportunity to reflect or even engage in buyer’s remorse as the pace of gaming is so fast; the loot box is opened, its contents delivered and the game moves on. Moreover, the nature of gaming as ‘social currency’ amongst teens means that there is no reasonable excuse for not buying the loot box – it’s not as if you have to walk to a shop to purchase a pack of cards or ask your parent to buy one for you. You’re there, in the game, often with your friends, making decisions in real-time.

Question d. Whether any harms identified may also apply to other types of in-game purchases

Parents are concerned about all in-game spending. 46% of Mums vs 39% Dads say they prevent their children from spending in games and 37% of parents say they should do this, rising to 41% of parents of children aged 4-6 years and 44% of parents of children aged 6-10 years. This is for the reasons we have already identified about uninformed consumption, the immediacy of decision making, investment in intangibles (which unlike offline experiences cannot be easily shared) and understanding the value of money. Additionally, schoolchildren told us through the Cybersurvey about their spending habits. Over half (58%) of the 11-year olds never spend money on games. But 15% often spend ‘quite a bit of money’ and a further 27% have done so once or twice. In-game spending increases in the mid-teens, 14-year olds are the most active with almost 1 in 5 often spending quite a bit of money in online games, a further 28% have done so once or twice. This pattern stays steady with age, as 21% of 16-year olds often spend money in games, with a further 26% saying they have done so once or twice.

School-aged frequent in-game spenders feel more confident behind a screen than non-spenders (36% vs 15%) and say ‘the internet gives me personal freedom’ (56% vs 25%). They are more likely than non-spenders to say ‘I feel like other people when I am on a screen’ (24% vs 9%,) and to say ‘my online profile is better than my real self’, (20% vs 9%). So perhaps children frequently spending in games should be an indication that they may need some support with other issues in their lives.

The consultation also asked about PEGI ratings:

As with all things parenting, there is a normative view, and there is the reality of parenting which, in relating to PEGI ratings is neatly summed up by this quote from a Mum of an 11-year-old boy:

“Alfie plays Grand Theft Auto online at the moment and needless to say I’m not entirely happy with the adult content. I’ve resisted buying him the game for a number of years but he’s at an age now where all his friends have it and he’d feel left out if he didn’t have it.”

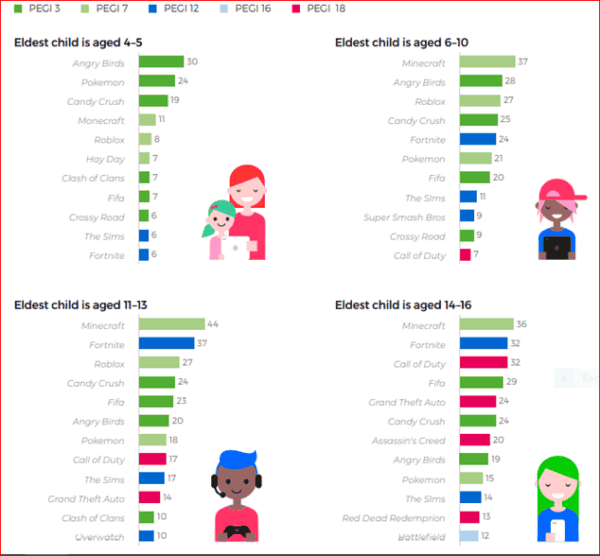

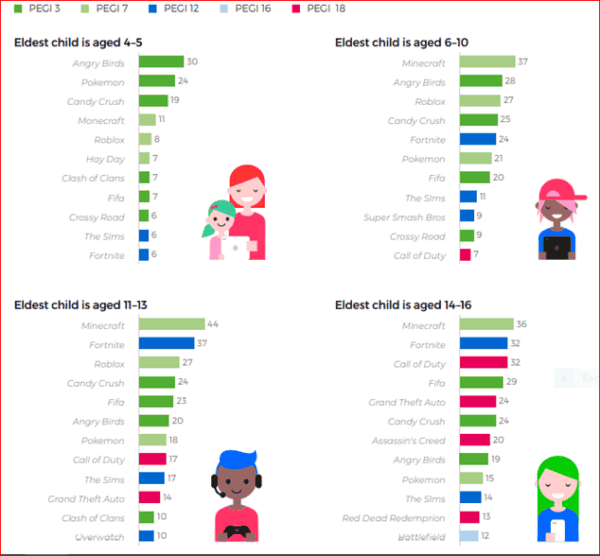

Of course, parents know that giving their children access to games that are created for adults, with all of the content risks that entails is not ideal. And yet, in answer to this question: Which games are you aware of that your eldest child plays either on mobile devices or on PCs and consoles? , parents told us that they regularly allow their children to play games rated for older children. When we questioned parents on why they did this, the answer was a simple “as it was uniform”. Gaming is a social currency at school. If your secondary school-age son is not playing the right games, there is a real risk that he will be socially isolated at school, with absolutely nothing to contribute to any conversation outside of class.

This isn’t a positive parenting decision – it’s the result of an invidious choice between permitting your child to experience content that you are unhappy about or effectively ensuring your child is socially isolated at school. If there are 12 million children in the UK, this data suggests that tens of thousands of parents are voting for older content over social isolation.

If Call of Duty (PEGI 18) is played by 17% of 11-13-year olds and 32% of 14-16-year olds, questions should be asked in two areas. Firstly, how effective are the PEGI ratings and secondly, who needs to do what to counteract the compelling social pressure so that parents are not faced with this decision of despair? It’s not good enough for gaming manufacturers to hide behind ratings they know are not working and not tackle the in-built compulsion in the products they market that pull in younger children. Perhaps in addition to the elements that are currently rated, the level of compulsion could be rated. Could there be a rating of the design metrics included to hold your attention or the intensity of input into loot boxes to ensure the percentage purchase rate is sufficiently high to create a meaningful revenue stream? And if not, why not?